As someone who reads a lot of books, it’s my job to sagely insist that books are better than films. This is no more definite than when a book has been adapted into a film. We - the book lovers - are tasked with lining up in our droves to watch it, only to emerge into the bright lights of the cinema foyer, smugly declaring: “The book was much better.”

Unfortunately, I don’t think that’s always the case. There are bad adaptations of good books, yes. But there are also good adaptations of good books and good adaptations of bad books. There are probably also plenty of bad adaptations of bad books, although I’ve tried to avoid seeing too many of those.

Throughout the first six weeks of this year, I’ve seen three book-to-film adaptations in the cinema. In every case, I’ve really enjoyed the film. So much art is inspired by other art. Nobody would write off the sculpture on the piazza outside the British Library as just an adaptation of a William Blake painting; nobody would write off Tracy Chevalier’s Girl with a Pearl Earring as just a novelisation of a famous portrait. If a writer or director reads a books which speaks to them, wants to translate it to the screen and can do it well, I welcome that.

Poor Things by Alasdair Gray (1992) / Poor Things dir. Yorgos Lanthimos (2023)

For my first adaptation, I started with the book, which may well have been a terrible mistake. In short, I hated it. I’m trying to keep my social media presence positive and be less of a hater, so I won’t delve into every little thing I disliked about Gray’s novel, but suffice to say I found it painfully pompous and self-indulgent. Poor Things tells the story of Bella Baxter, a woman ‘saved’ from death following the medical intervention of Dr Godwin Baxter. She is effectively reborn and must learn how to do everything anew: walking, talking, behaving nicely in polite society. Despite her obviously infantilised state, she is the object of desire for every man she meets. In fact, she is ‘what men have hopelessly yearned for throughout the ages: the soul of an innocent, trusting, dependent child inside the opulent body of a radiantly lovely woman’ - an idea which gave me a permanent ‘ick’ throughout my reading experience.

By the time I got round to a planned cinema trip with my book club to watch the film, I was dreading it. Luckily, I was pleasantly surprised. The film still harbours the elements of the novel I found grim, largely centring around a group of adult men fighting over who gets to have sex with a girl with the mental age of a toddler. But Emma Stone is Emma Stone and so her performance of Bella Baxter was gorgeously rendered, bringing a new life to the relatively two-dimensional figure of the book. Most of the novel involves people (men) talking about Bella, whereas the film script seemed to give her much more of a voice. Mark Ruffalo was also brilliant as Duncan Wedderburn, a character I had very little interest in while reading his section of the source material. It was an unexpected treat to see Kathryn Hunter playing brothel owner Madame Swiney, having watched her incredible performance as Janina in Complicite’s stage adapatation of Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead last year. The costumes, set and cinematography were beautiful, and although I could have done with about 20 less sex scenes (I’m not a prude, I just find them painfully boring) I found the film really striking and fun.

The End We Start From by Megan Hunter (2017) / The End We Start From dir. Mahalia Belo (2023)

I first read Megan Hunter’s The End We Start From in 2021, the year I really got back into reading as an adult. I loved it then and was delighted to hear it was being adapted into a film starring the ever-impressive Jodie Comer. I didn’t remember all the intricate details, but felt I’d retained enough to have a decent idea of the plot.

In The End We Start From, we follow an unnamed woman trying to survive an urgent ecological crisis with her young baby in tow. The film was really well done, balancing the external threat of climate change with the internal struggles and rewards of new motherhood in exactly the way I remembered admiring in the book. Certain images - especially the first few scenes - will stay with me for a really long time. Jodie Comer was obviously brilliant, but it’s Katherine Waterston as ‘O’ (another new mother who Comer tentatively befriends on her journey) who I’m still thinking about.

After watching, I felt compelled to re-read Hunter’s novel and was heartened to find there was still so much to love about it. My reading tastes have changed a lot over the last few years and, having read a lot more widely, I have often found myself disappointed when returning to old favourites. The story is told in fragmentary fits and starts, reminiscent of prose poetry. Descriptions are scant, with characters only identified through single initials. You get the kind of words that work brilliantly on the page but wouldn’t translate on screen: ‘Between the waves of disemboweling wrench, the world is shining. I feel like Aldous Huxley on mescaline. I am drenched in IS-ness.’

I love Hunter’s sparse and dreamlike prose and I love Belo’s more solid and tangible interpretation of it. To me, this is an example of how both the book and the film can be great in their own ways; the story remains the same but we are invited to look at it from two different perspectives.

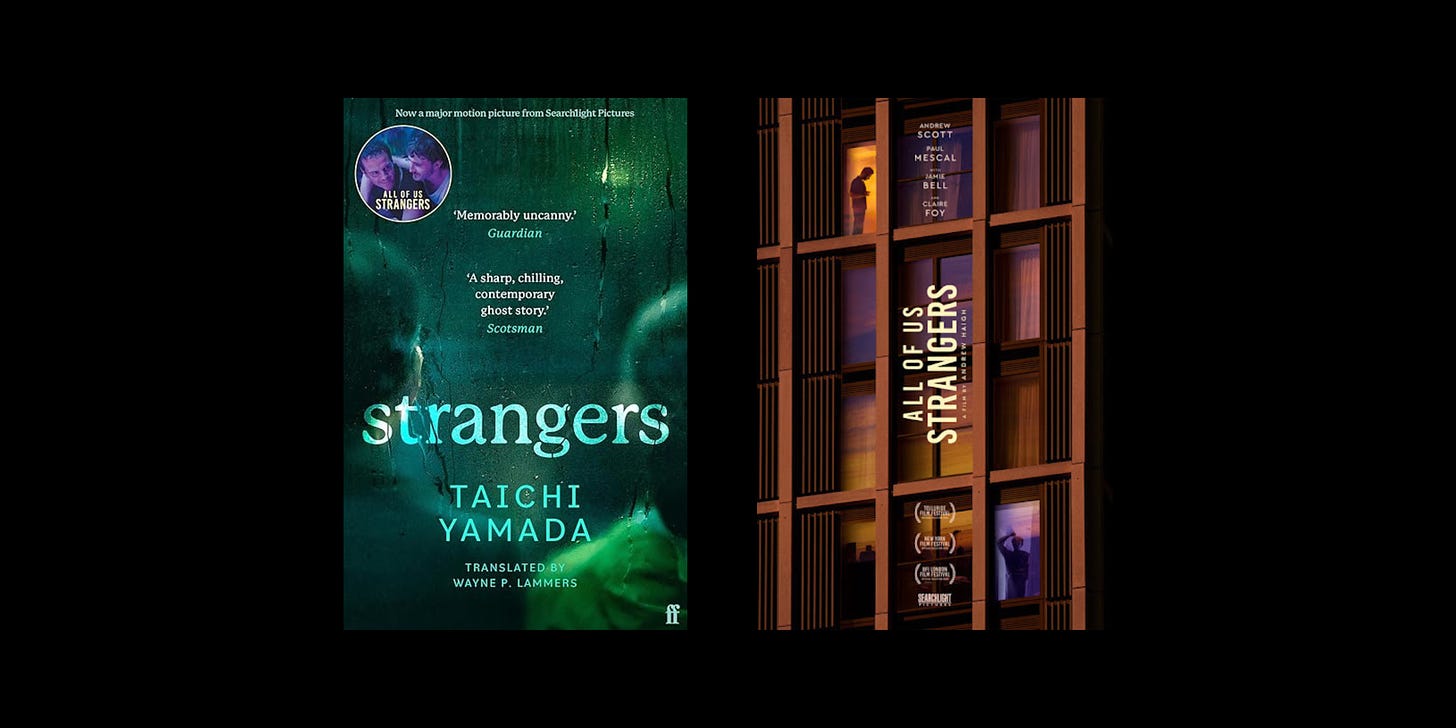

Strangers by Taichi Yamada (1987) / All of Us Strangers dir. Andrew Haigh (2023)

This time round, I watched the film first. I am firmly of the belief that Andrew Scott is one of the best actors working today, and I expect to love pretty much anything he is in. I didn’t want to sully the experience with the potential of negative bias (still haunted by memories of Poor Things) so I arrived at the cinema with only the vague patchwork premise offered by the trailer and left the book for later.

Obviously, I loved this film. It’s sad and gentle and hopeful and bleak. I hate it when reviewers describe things as ‘tender’ but this was genuinely pretty tender. I cried so many times that it essentially just became one long cry. To give too much away would ruin it, but in short it is the story of lonely 40-something screenwriter Adam (Andrew Scott). Two strange things happen to him at the same time. Firstly, he takes the first steps into a relationship with a younger man who lives in his apartment block. Secondly, he visits his childhood home and is greeted by his parents, who have been dead for 30 years.

I loved it so much that I started reading the book almost immediately. Luckily, this wasn’t a repeat of the Poor Things incident. I liked the book. Admittedly, I didn’t love it in the way I loved the film, but that’s fine. It’s very different to the film - a very loose adaptation in most senses - and it’s Haigh’s interpretation that I prefer, but it’s Yamada who deserves credit for a really good central idea.

The most notable difference between book and film is the queerness. In Yamada’s original story, the narrator (also a screenwriter in his late 40s) starts a relationship with a younger woman, rather than a man. The queerness of Haigh’s reimagining fits in so well with the exploration of grief and loneliness at the heart of the story that it’s hard to believe it wasn’t there to begin with.

The film adaptation also brings the narrative into a world that is familiar to me. I’ve never been to Tokyo but I have spent a lot of time in London. I’ve never sat in a Japanese variety show, but I have been to my fair share of dodgy British nightclubs. Strangers is told from the perspective of a man nearing the end of his forties, whereas Paul Mescal is younger than me and brings a kind of quiet sadness to his role that I can recall from less happy times in my 20s. There is a haunting loneliness in the London high rises that I feel I understand, which perhaps gives me a more personal connection to the framing of Haigh’s film than I was able to establish with the book.

So, is the book always better?

Film adaptations can never include every detail of their source material. I think that’s a good thing. Through what writers and directors choose to keep, discard and change, we learn something about what the central narrative means to them. We can see stories through the eyes of others. For example, if anyone but Andrew Haigh, a gay man from the north of England, had adapted Strangers, it would be a completely different film. In the production notes, Haigh says: ‘I wanted to pick away at my own past as Adam does in the film. I was interested in exploring the complexities of both familial and romantic love, but also the distinct experience of a specific generation of gay people growing up in the 80s. I wanted to move away from the traditional ghost story of the novel and find something more psychological, almost metaphysical.’ We see the story through his eyes and this brings something new to it.

Films and TV also introduce us to books we might not otherwise encounter. I might never have read Strangers were it not for watching the film. Recently, I bought my partner a copy of the Benjamin Myers novel The Gallows Pole after we watched Shane Meadows’s TV adaptation, a book I know he would never have otherwise picked up. I’m about to start reading Erasure by Percival Everett because I loved the recent film adaptation American Fiction.

Having considered three books (one I loved, one I liked, one I hated) and three films (all of which I really enjoyed) it doesn’t seem to me that the book is always better than the film. Writers and directors are all in the business of telling stories and I’m firmly of the belief that the more stories we have and the more perspectives we can see them from, the better.